excerpts from Sweet Invention

Sacred Fudge

Manasollasa

Unfortunately, most documentary evidence of the early history of food in India comes in such tattered scraps that it’s hard to assemble it all into a meaningful whole. There does exist, however, a large, richly embroidered tapestry that details the feasts and other entertainments of at least one medieval Hindu potentate. Sometime around 1131, King Sômēśvara III sat down to pen a handbook on how to run a kingdom that came to be known as the Mānasôllāsa. Sômēśvara’s realm, the western Chalukya empire, was enormous, covering a large swath of southern India. In his how-to manual, the king went into enormous detail, covering everything from alchemy to military strategy to issues of taxation. He gave advice on religious topics, interior design, and child rearing. He listed varieties of umbrellas and the best kinds of beds. (This last item was clearly of great concern to the author given his affection for the fairer sex.) Not only are there rules for work, there are instructions for play. Sômēśvara dwelt at length on what the monarch should do on his days off. According to the Mānasôllāsa the ideal ruler should spend most days frolicking in fragrant gardens and playing hide and go seek with beautiful women. Perhaps so he can work up an appetite for lunch?

With his hedonistic temperament, it is to be expected that Sômēśvara would have plenty of opinions about food and dining. It seems, for example, that the monarch was much taken with eating en plein air. A royal picnic demanded a sensual setting, amid beautiful farms or pasture grounds, aromatic with flowering trees and plants, “the air full of the fragrance of ketaki flowers,” which the author found especially suggestive. In this idyllic location the thump of elephants brings on erotic thoughts and the peacocks mimic the sound made by the flying arrows of the Cupid-like Manmadha. The royal servants prepare the spot with carpets and tents to greet the monarch as he arrives on an elephant decorated with flowers, golden bells, and vermillion powder, surrounded by his women, “who shine with jewels.” There are singers and dancers—and more women. When the ruler and his lovers dismount they are feasted with “a variety of tasty items.” He then gives away jewels, flowers, and clothes to his concubines. Song and dance fill the rest of the afternoon until the party finally departs for home. In this particular case, the author leaves the details of the romantic afternoon somewhat to the imagination. Elsewhere he is more graphic. In medieval India, sugar wasn’t merely used in confectionary. It was also fermented into an alcoholic toddy. Apparently Sômēśvara enjoyed getting his lovers drunk “for relaxation and satisfying his sensual feelings” so that he could “enjoy the different moods of the intoxicated women.”

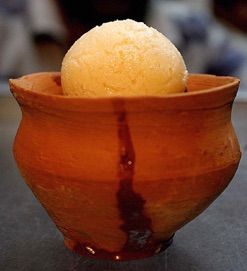

He was also cryptic about the “tasty items” served at the picnic, but his meals must have been a delight. In another passage, his model king is directed to sit on a cushioned seat, his lap covered by a large white napkin. The food arrives on a great platter of gold. First there is rice with a kind of dal made of green lentils, then tender meat with more legumes and side dishes of vegetable curries. There is a pause in the middle of the meal for pāyasam (sweet rice pudding) before proceeding to other savory preparations. The pāyasam is the only dessert he mentions in the context of a meal, though elsewhere he describes the preparation of many others. Perhaps among these were the tasty items served at his outdoor fête.

❁ ❁ ❁