excerpts from Sweet Invention

A Democracy of Sweetness

Wedding Cake

Today, the wedding cake is just about the only confection that still conjures up the glory and folly of the baroque confectioner’s art. Weddings are one of the few occasions when wealth and power are still calculated in layers of sweet fondant. At a fancy society event, the cake can run into thou- sands of dollars.

Collection of the New York Public Library

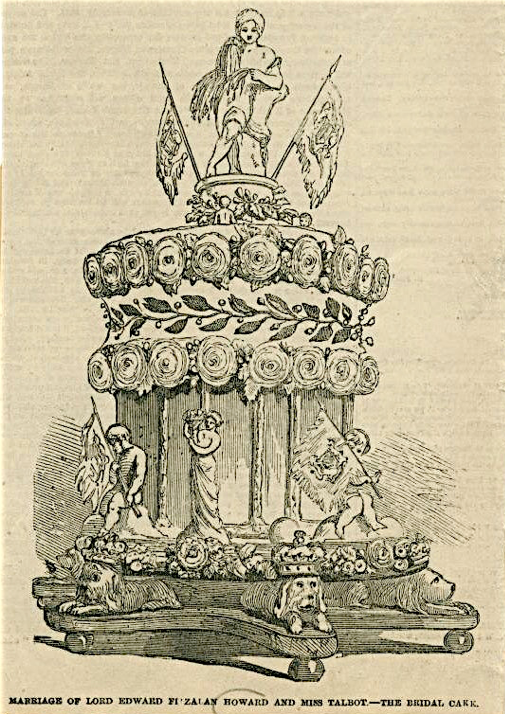

Caught up in the fury of the Civil War, Americans didn’t pay much attention to that particular pastry edifice. It was the next royal wedding cake that caught their notice. This was one of two giant cakes created by Queen Victoria’s chief confectioner for the wedding of Edward’s sister Louise. (The cakes were likely the work of Alphonse Gouffé,

the brother of one of Carême’s star pupils, Jules Gouffé.) One of the cakes was widely reproduced in popular publications. Newspapers reported that it was over five feet high and weighed in at 225 pounds. It was surmounted by a miniature classical temple topped off with an image of a vestal virgin, while allegorical figures of Agriculture, Fine Arts, Science, and Commerce stood round the base. What it lacked in romance, it made up for in classical tastefulness. Every American bride who dreamed of being a princess now knew just the kind of cake she should have for her wedding. These sugary monuments, along with the white gowns popularized by Victoria’s princesses, became all the mode in the mansions of Fifth Avenue and Beacon Hill. In fact, the cake and the dress came to resemble each other: both white, both virginal. A contemporary description of Princess Louise’s wedding dress could easily apply to the multi-tiered wedding cakes of the coming generations: “The bride was dressed in white satin . . . with ornaments of orange blossoms and green leaves and a cloud of . . . lace.” About a dozen years later, American cookbook author Estelle Woods Wilcox explained how bride’s cakes should be placed on lace paper, adding, “It is not imperative that you use orange blossoms in the decorations of a bride’s cake, still it is usually done.” By this point the term “bride’s cake” had been revived in the United States to describe a white cake that might be served alongside (or increasingly instead of) the old-fashioned wedding fruitcake.

Earlier bride’s or wedding cakes (or dresses for that matter) didn’t used to be white. One popular English cookbook of the early nineteenth century specifically advised dyeing the icing red (or pink) with cochineal. Writing in post–Civil War America, Mrs. Wilcox insisted that only white icing was now permitted. Then, as now, it was often inedible. An American trade journal around the turn of the century took this in stride, noting that the sugar curlicues were there for decorative purposes, adding, “bride cake icing is hard and unpleasant to eat.” Wedding cakes are so packed with symbolism that it is hard to know where to begin. A writer for Godey’s Lady’s Book commented in 1831 how, as in marriage, the sweet exterior was only camouflage for the “crusty humour beneath.” A contemporary English writer expressed the sentiments in slightly different words: “The bride cake is composed of many rich and aromatic ingredients, and crowned with an icing made of white sugar and bitter almonds, emblematical of the fluctuations of pleasure and pain which are incidental to the marriage state.”

The significance of the Victorian era’s virginal white is all too obvious, yet the ceremonies surrounding the cake didn’t always used to be so chaste. One ritual common in eighteenth-century Britain took place after the cake had been cut up. In this “idolatrous ceremony” (as The Gentleman’s Magazine dubbed it in 1832), the bride holds the ring between the forefinger and thumb of her right hand while the groom repeatedly thrusts small pieces of cake through the opening. These are then distributed to the bridesmaids. As British anthropologist Simon Charsley has pointed out, the ritual of the newlywed husband and wife plunging the knife through the virginal exterior symbolically consummates the marriage. But that isn’t the end of it. Like marriage, the cake was supposed to last forever, and accordingly brides would save a fragment for posterity. Unsurprisingly, many of these stale crumbs have outlasted the marriages, or in some cases even the brides. In 2009, a slice of Princess Louise’s famed wedding cake hit the auction block for an asking price of £145. The seller warned that it was not safe to eat.

❁ ❁ ❁